Author Interview: The Creators of the New Roots/Nuevas Raices Oral History Initiative

In their recent OHR article, “Migration and Inclusive Transnational Heritage: Digital Innovation and the New Roots Latino Oral History Initiative,” Hannah Gill, Jaycie Vos, Laura Villa-Torres, Maria Silvia Ramirez demonstrate how the New Roots Latino Oral History Initiative engages with and documents immigrant populations. Here Gill answers a few of our questions about the project.

Briefly tell our readers about the New Root/Nuevas Raíces Oral History Initiative and its goals.

The New Roots Latino Oral History Initiative is an ongoing research and archival initiative started in 2007 by the Latino Migration Project, a collaborative program of the Institute for the Study of the Americas and the Center for Global Initiatives at UNC-Chapel Hill. The oral histories are archived with the Southern Oral History Program’s collections in the University Libraries. New Roots documents the arrival of Latino communities in the U.S. South, one of the most significant demographic changes in the recent history of the nation. We recently created a digital information system and bilingual website to enhance global access to the oral histories of migrant newcomers.

How have the digital technologies the projects used facilitated the work of oral history?

Using the open-source software Omeka, we created a new website and tools to map migrant journeys, sync data from institutional archival systems, and facilitate the online presentation of content in two languages.

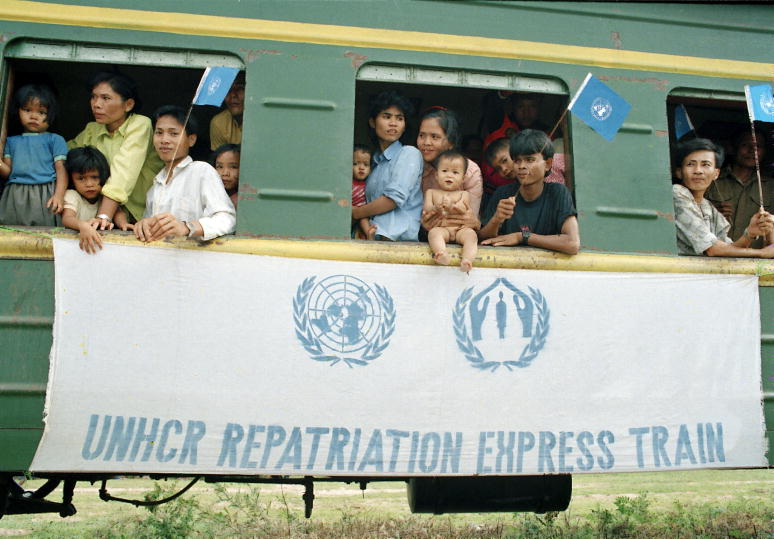

As the United States and other countries experience more demographic changes in the 21st century, how can the New Roots Latino Oral History Initiative adapt to, reflect, and address those changes?

There are many ethical and methodological challenges of engaging with internationally mobile populations and in new destination regions where migrants face linguistic, socioeconomic, and legal challenges that hinder access to the resources of educational and governmental institutions. Our work is committed to engaging with migrant communities to address these challenges and open access to resources. For example, the New Roots website was designed collaboratively with migrants, Latin American scholars, and K-12 teachers, and most of our interviewers have recent Latin American ancestry.

What is the relationship of the project to current legal and policy battles over immigration?

Oral histories in New Roots reflect critically upon the current immigration policy landscape, describing life during a time of unprecedented deportations, border enforcement, and local immigration policy and programs. Oral histories describe efforts to pass comprehensive immigration reform and access to higher education on federal, state and local levels.

Describe the targeted and potential audiences for the project.

New Roots responds to a growing demand for oral history resources from constituencies that include North Carolinians with Latin American heritage, K-12 teachers in Mexico and Latin America, museums and heritage centers in the U.S. and Latin America, civil rights and youth mentoring organizations, and scholars and journalists throughout the Americas.

Please explain the significance of the project’s bilingual aspects.

New Roots uses a bilingual system of description and arrangement, and outreach to make the New Roots materials more accessible to regional, national, and global public constituencies both north and south of the U.S.-Mexico border. Many of the New Roots oral history interviews are conducted by bilingual graduate and undergraduate students as part of an annual interdisciplinary course that combines ethnographic and oral history methods, migration theory, and service-learning to understand Latin American migrant perspectives. Students’ long-term service experiences, academic training, and bilingual skills enable them to build relationships that facilitate oral history collection in migrant communities, and many continue this engagement after the course.

How can the project assist those who may not have access to high-speed internet?

New Roots materials can be downloaded as mp4s and pdfs, so they can be exchanged on usb drives when streaming is not available. We do storytelling workshops with K-12 schools that do not involve the internet.

What are your hopes for the future of this project?

We hope to reach more global audiences with these resources and partner with community organizations to offer content.