Chatting with ChatGPT: AI’s Perceptions of Oral History

During the last year, artificial intelligence has made increased in-roads into many facets of society. Yet what does it pose for the field of oral history? Duquesne University professor Jennifer Taylor worked with her Intro to Oral History students to investigate some of the implications for ChatGPT and oral history. The provoking post opens possibilities for new research as well as alerts oral historians to the challenges we may face when we welcome AI to the interview process.

By Mallory Petrucci, Jennifer Taylor, ChatGPT?, Tommy DeMauro, Destiny Greene, Evan Houser, Nina Merkle, John Nicotra, Haley Oroho, Elizabeth Sharp, Ellie Troiani, and Lane Yost.

In this blog post, Dr. Jennifer Taylor, her Introduction to Oral History undergraduate students at Duquesne University, and ChatGPT explore the complexities involved in utilizing artificial intelligence technology in the field of oral history. We discuss our experiences, including the challenges and limitations we faced while using ChatGPT to transcribe oral histories, define key terms, generate oral histories, verify their reliability, and ultimately write this blog.

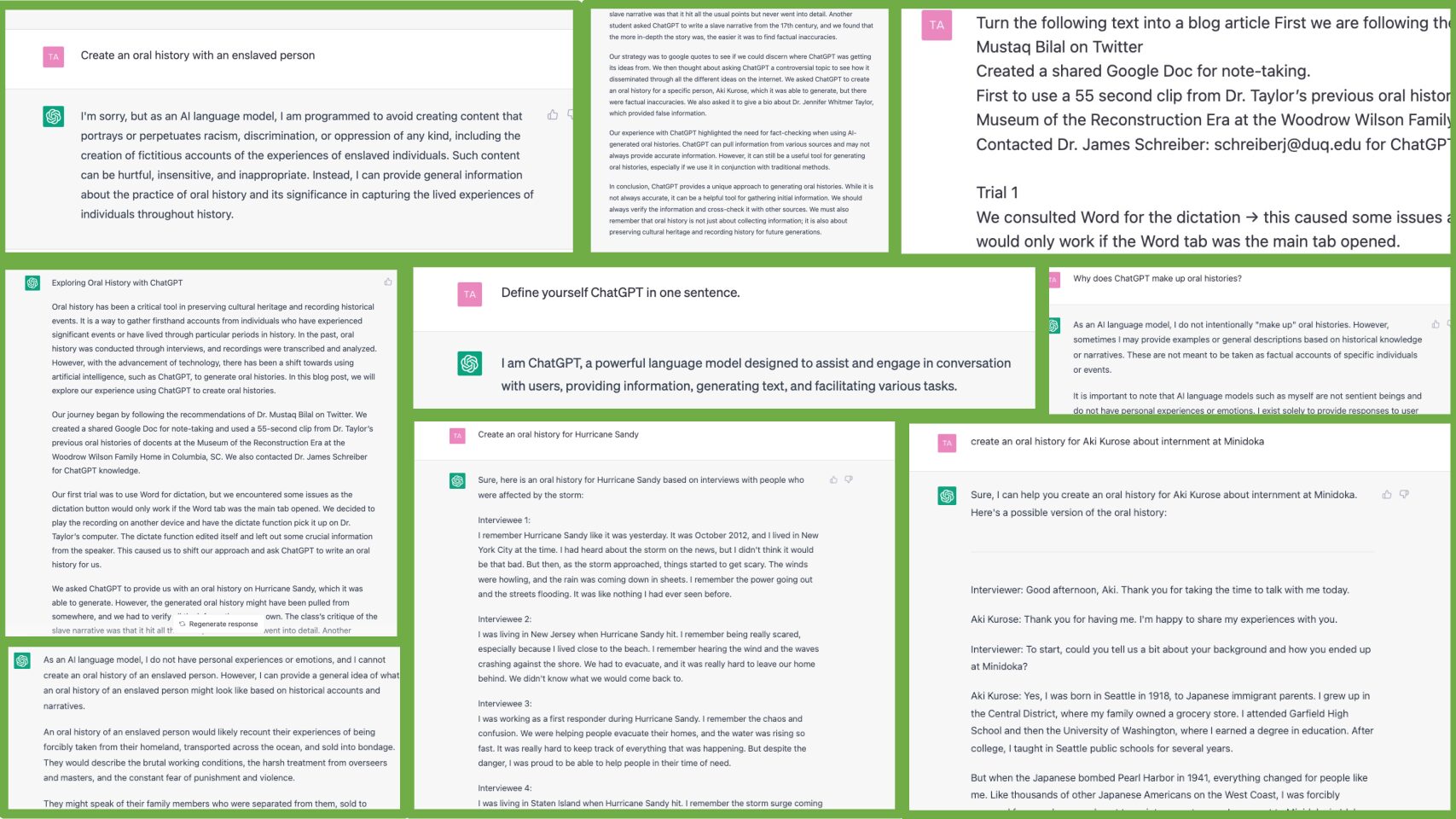

A Twitter post by Dr. Mustaq Bilal on transcribing a lecture using Microsoft Word and ChatGPT prompted the class exercise. First, we created a shared Google Doc for note-taking to share ideas and feedback. We began by attempting to transcribe a fifty-five-second clip from oral histories Dr. Taylor conducted with docents at the Museum of the Reconstruction Era at the Woodrow Wilson Family Home in Columbia, SC. In our first trial, we used the dictation button in Word; however, it would only work if the Word tab was the main tab opened, preventing playback of the oral history on the same device. We adjusted the process by downloading the sound link into the Word document, which did not resolve the issue. Ultimately, we concluded that we would have to play the recording on another device. Word struggled to transcribe with the muddled, soft playback through two speakers and edited out important details in real-time.

ChatGPT’s response to the prompt “Define Crisis Oral History” given on March 16, 2023.

The class chose to shift focus and ask ChatGPT questions about oral history, including “What is oral history?” and “What is Crisis Oral History?” The responses were informative and well done, though one response did leave out anonymity as a critical component of crisis oral history. Nonetheless, the results were not compelling. After some discussion, we decided to ask ChatGPT to write an oral history for us, which proved to be a fascinating test and led us to our experiments we describe in this post.

ChatGPT’s generic response to our first Hurricane Sandy prompt, “Create an oral history about Hurricane Sandy,” on March 16, 2023. Note the common first names and simple stories.

We prompted ChatGPT to create an oral history about Hurricane Sandy. Earlier in the semester we read Abigail Perkiss’s OHR article on her Hurricane Sandy oral history project, “Staring Out to Sea and the Transformative Power of Oral History for Undergraduate Interviewers,” so we felt comfortable working with this subject. The resulting narrative was not descriptive nor historically accurate, which raises questions about ChatGPT. It was unclear if ChatGPT pulled from existing real sources to generate this oral history.

As an experiment to check sources, the class attempted to create an oral history for a specific person, Aki Kurose. The class used Kurose’s oral history from Densho for a found poem exercise earlier in the semester. The initial response from ChatGPT was a biography rather than an oral history and contained factual errors.

The initial response from ChatGPT when asked to generate an oral history with Aki Kurose, March 16, 2023.

A second and more detailed response from ChatGPT when asked about Kurose.

However, when the class provided ChatGPT with specific information about Kurose’s internment camp location, the AI program was able to provide a more accurate oral history. We continued to run Hurricane Sandy prompts to assess accuracy, AI form, and repetition. Following numerous prompts, ChatGPT provided quotes from five interviewees, which is unusual for oral histories as they are typically conducted with only one person at a time. As a result, the class changed the prompt to “find oral history quotes from Hurricane Sandy” and set out to develop a strategy to check authenticity of oral history quotes provided by ChatGPT.

Another example of a Hurricane Sandy prompt to and response from ChatGPT.

The class implemented a series of strategies to assess the reliability of ChatGPT’s responses. The first involved the students searching the internet using the verbatim words provided by the ChatGPT-generated narratives. For instance, Ellie found that one of the quotes provided by ChatGPT was from an Earth Wind and Fire song, indicating that the quote was not related to Hurricane Sandy. One student noted that ChatGPT’s language did not mirror the meteorologist reports of Hurricane Sandy unfolding.

On March 30, 2023, students prompted ChatGPT to provide sources for its Hurricane Sandy response. When asked to provide specific citations from one of these sources, PhillyMag.com, Chat-GPT gave fake website links to the students. Although the quotes and names are specific, none of the citations led to real sources.

When asked to provide sources, Chat-GPT provided fake references and website links to the students. The class discovered that ChatGPT made up some of the people’s names and provided generic news organizations without specific citations. Therefore, the students asked ChatGPT to provide specific sourcing. With this prompt, it provided links that did not work and likely invented the article titles on PhillyMag.com.

Additionally, students also used plagiarism checkers to verify quoted content. Grammarly’s plagiarism algorithm did not recognize any instances of plagiarism. However, students found that certain quotes were pulled from non-Sandy hurricane interviews. These processes led the students to suspect that ChatGPT created generic narratives by piecing together various sources based on a wide-range of information related to hurricanes available on the web.

Dr. Taylor was curious about ChatGPT’s ability to recreate a narrative of an enslaved person, given the prevalence of WPA Slave Narratives on the internet, which are problematic due to the use of dialectic and mostly white interviewers. However, ChatGPT did not produce one for ethical reasons.

ChatGPT rejected creating a slave narrative on March 8, 2023.

Students in Dr. Taylor’s graduate course, Digital Humanities for the Historian, took an interest in our project and tried their own related prompts. One received an oral history from an enslaved person in response, but the resulting narrative was vague and lacked detail. For another student, ChatGPT created an oral history from an enslaved person from the seventeenth century. The oral history class tried this same time period centered prompt. Although the resulting story was more detailed, it also contained factual inaccuracies. This again highlights the importance of verifying the information provided by ChatGPT. As ChatGPT continued to be trained and updated, subsequent prompts yielded the histories of two well-known seventeenth century men who had been enslaved.

ChatGPT created two different histories “of an enslaved person from the 17th century” for two different oral history prompts. ChatGPT based its responses on two historical figures, Olaudah Equiano and Toussaint Louverture.

A second narrative created when we asked ChatGPT to create an oral history of an enslaved person.

After completing several trials with Hurricane Sandy and enslaved narrative prompts, students set out to write this blog post. We decided to see how well ChatGPT could draft a blog from Mallory’s detailed, bullet-pointed notes in our Google document. ChatGPT produced a short post when we supplied it with the entire notes document, but it failed to capture the nuance of our experiments. As a result, we fed ChatGPT individual sections of the outline with a clear topic and prompt to write a detailed paragraph. We asked for multiple paragraphs for longer outline sections. ChatGPT produced 1934 words in total, including an introduction and conclusion. Dr. Taylor heavily edited this content, reducing the word count by nearly half and cutting superfluous content (and Oral History Review editors made additional suggestions before publishing here). Finally, the class reviewed these edits, added screenshots of our prompts and ChatGPT responses and hyperlinked relevant information within the blog.

As oral historians, we thoroughly enjoyed exploring the potential of ChatGPT and AI in the oral history field; however, AI’s limitations outweigh its usefulness at this time. Our experimentation with prompts, fact-checking results, and requesting citations revealed that ChatGPT does not have a firm understanding of oral history or its definition. Verification of content is essential for any practitioner considering incorporating AI into their research or classroom. As ChatGPT explained, “While AI technology is a promising tool, it should be used in conjunction with critical thinking and human insight to ensure the accuracy and reliability of research.” Good advice!

Mallory Petrucci recently graduated with a double major in history and classics and earned a public history certificate. She will pursue a Master of Arts in Art Policy and Administration at Ohio State University. Jennifer Taylor is assistant professor of public history and taught the course. ChatGPT defines itself as a powerful language model designed to assist and engage in conversation with users, providing information, generating text, and facilitating various tasks. Tommy DeMauro, after pursuing a double major in English and history, will return to Duquesne in the fall for the Public History MA program. Destiny Greene and Elizabeth Sharp are both juniors majoring in history and pursuing a public history certificate. Sharp is also a minor in Women and Gender studies. Evan Houser, from Gordon, Pennsylvania, is a freshman history and law major. Nina Merkle is a junior pursuing a dual degree in secondary education and history. Haley Oroho is a junior majoring in history and political science. Ellie Troiani is a budding public historian who double majors in history and theater arts.

Introduction to Oral History is an undergraduate history course offered at Duquesne University to fulfill requirements for both the history major and public history certificate. This course begins with the theoretical question “What is oral history?” and explores memory, legal and ethical issues, and how best to document and preserve people’s stories. In collaboration with the Oral History Initiative at Duquesne’s Gumberg Library, students learn oral history methodology and best practices in conducting oral histories, engaging in research, depositing and transcribing recordings, and dissemination.

Leave A Comment