Author Interview: Renata Schellenberg on “Composing the Blue Book”

In OHR’s spring Issue, scholar Renata Schellenberg analyzes the Blue Book, a document dependent on oral testimonies that reported the abuses that native South West Africans suffered under German colonial hands. Her study provides a new perspective on the Blue Book by critically analyzing the political intentions of the document and the historical circumstances of the time. “Composing the Blue Book: The Use of Oral Sources to Narrate German South-West Africa” moves South-West African history forward, by adding a new interpretative lens to this valuable primary source. Schellenberg answered our questions about the Blue Book and its significance in her author interview.

Please describe the Blue Book, Report on the Natives of South-West Africa and their Treatment by Germany and its significance to Southwest African history.

The Blue Book is an important document for German South West Africa (GSWA) as it provides a seemingly comprehensive and objective overview of the colony until 1918. This formal government synopsis included economic, geographic, and demographic data, but it also featured a record of the many abuses suffered by the indigenous people in GSWA by German colonial powers. In my view, the inclusion of this contentious information greatly expanded the purview of the Blue Book, by creating a veritable document of violations committed by the German Imperial government – a document that could later be used by historians and scholars to ascertain what happened in GSWA prior to 1918. It is an archival resource.

How does the Blue Book use oral testimony, and what are your critiques of using such sources in this governmental publication?

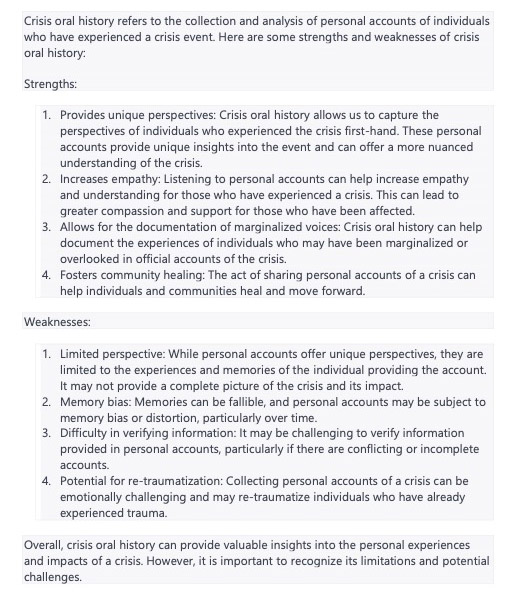

The Blue Book draws heavily on oral sources to convey the injustices that happened among indigenous groups and the German colonial government. An interesting fact is that the editors collected eyewitness testimony from both white and Black inhabitants of the colony to make the case that this colonial violence occurred. I interpret this approach as quite progressive, as it signaled a certain equality among members of the Black and white population in GSWA when gathering this information – an equality which was certainly not the day-to-day reality. The use of oral sources as a key authoritative source of information for a government publication can also be somewhat problematic, as these sources are clearly not objective in the articulation of their experiences (nor should they be), but also because the information provided by these sources often cannot be verified through other existing archival means. The inclusion and omission of opinions of the government-employed editor of the Blue Book indubitably play a big role here and shaped the final version of the text.

How do you recommend analyzing perspectives from oral testimony while successfully detecting potential political aims and other objectives?

In order to detect, minimize, and mitigate possibly biased recordings of oral testimony (political or otherwise) it is important to learn as much as possible about the context in which such testimony was gathered. The perspective of the initial interviewer is very important as it can determine the intended use of oral testimony (in print and elsewhere). An informed understanding about the underlying cultural, social and historical circumstance of the interview are therefore important. This knowledge helps identify possible manipulations of oral testimony and helps garner an objective reading of the oral testimony provided. I think this is how the reader does justice to the actual interviewee in the process of gathering oral testimony.

Describe what happened when the Blue Book was republished in 2004.

The Blue Book was reprinted in 2004 on the 100th anniversary of the beginning of the Nama Herero War. The reprint was an significant endeavour as it allowed this information to be broadly disseminated to a new (and post-colonial) audience. The Blue Book was not easily accessible in Namibia during the Apartheid years, as the South African government did not want to agitate white German Namibians with the report’s implicit criticism of their colonial rule in GSWA and therefore, starting in 1926, removed copies of the report from public access. The reprint of the Blue Book in 2004 was thus a welcome occurrence, as it helped propagate data about the poor treatment of indigenous Africans to a broad readership, ensuring that this information was accessible to all members of society. Some historians who work on German colonialism and German colonial history criticized the appearance of the reprint, stating that the editors should have provided a more thorough analysis alongside the reprint to ensure that the reprint was properly read and understood. They also wanted more research to accompany the original text – to help elucidate the text.

You mentioned that O’Reilly, the author of the Blue Book, used various methodologies to construct a narrative of the German Colonial control over the South West African Indigenous populations. Describe your analysis of these methodologies and what you learned from them.

The British government commissioned O’Reilly to gather oral testimony and one needs to remember this point when reading the Blue Book, as he was obviously approaching the task from a very defined (and opposed) political vantage point and was thus biased in his reporting. Some scholars have commented on the blatant propagandistic nature of the report, and they may not be wrong in that assessment. The Blue Book is not ethnography and was written to denote flaws in German colonial governance, indirectly justifying the change in colonial rule. And while there are clearly archival and scholarly benefits from compiling this indigenous oral testimony – it created a durable historical document that others could use to learn about GSWA– there are also problems with this project. O’Reilly never clarified the criteria of selection used when compiling the testimony, i.e. how he decided which testimony to use and which to omit from the report. He also did not clarify whether he used a translator to conduct the interviews, or whether he conducted the interviews in local languages himself (highly unlikely). The final text is in English. Another matter that was not broached in the report is the lapse of time that occurred between narrating the event (1918) and the event itself. The Nama Herero War ended in 1908 so in many of the reported cases there was a 10-year gap between the event and the telling of the event. This passage of time may have impacted memory of the event and this delay should have been perhaps flagged for readers.

What can contemporary oral historians learn from O’Reilly’s use of oral sources?

I think that contemporary oral historians can learn a lot from some of the obvious omissions made by O’Reilly in his efficient, but flawed reporting. It is thus extremely important to demarcate the parameters and conditions of the interview, so that readers can envision and understand how the information was gathered. Respecting the agency of the interviewee is crucial in these situations and it somewhat obvious that O’Reilly did not fully enforce this principle. He presumably did not ask for explicit permission to speak to people, for example. That said, O’Reilly was not an oral historian and never purported to be any type of scholar. He was performing a perfunctory bureaucratic duty. As scholars, we are required to do better than that.

What was your inspiration to write about this topic?

As a scholar, I am interested in war writing and the documentation of conflict. I think such writing and information gathering is always inadequate because it is impossible to render the impact the experience of violence can have on the individual. Oral testimony (even when properly gathered and presented) attests to this premise of inadequacies and incompletion, because there are always significant gaps between narrating the experience and the experience itself. Trauma runs deep and cannot be fully conveyed in words. As a German scholar, I was intrigued to read a report of German colonial violence in English and to compare that report to other (German) sources and see the difference in reporting. I am also closely following the current reparation discussions taking place between Namibia and Germany, and an informed understanding of the violent events in the Nama Herero War (as narrated in the Blue Blue) helps clarify why this is such a complex process.

Dr. Renata Schellenberg is professor of German at Mount Allison University, Canada. Her primary specialization is German literature and culture of the long eighteenth century, and she has written extensively on topics pertaining to print and material culture of this period. More recently, she has worked in memory studies and cultures of remembrance in twentieth-century Europe, publishing a monograph, Commemorating Conflict: Models of Remembrance in Postwar Croatia, in 2016. In the same field of study, Professor Schellenberg is currently researching postcolonial commemorative practices in Namibia, a project that has been funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. She also received a fellowship at the Ethnographic Museum in Berlin to study colonial objects taken from Namibia.