Inside the Interview

Hot off the presses, the new OHR features a special section, Inside the Interview: The Challenges of a Humanistic Oral History Approach in the Deep Exchange of Oral History, co-edited by Andrea Hajek and Sofia Serenelli. Here, Hajek shares its origins and themes.

By Andrea Hajek

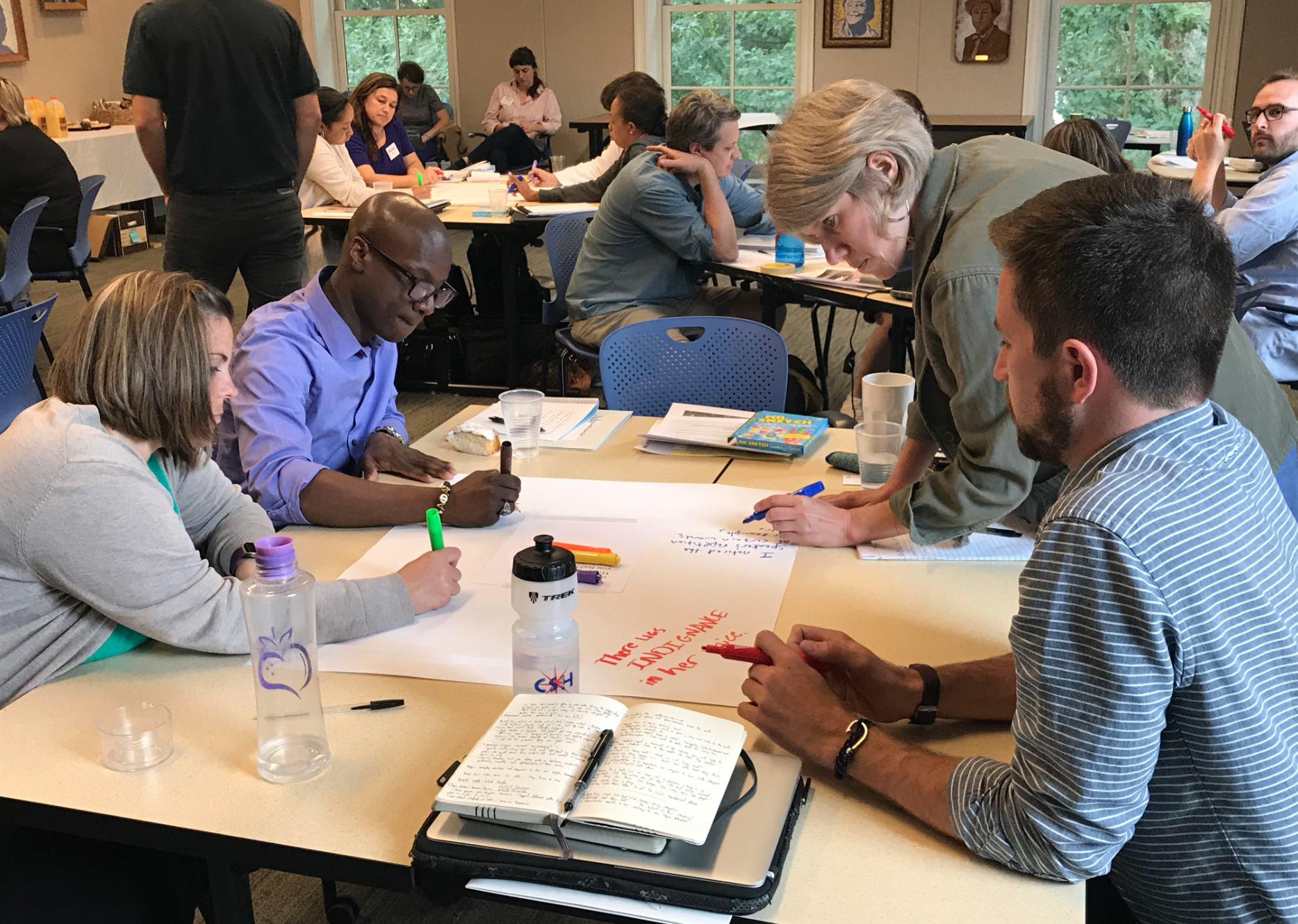

The idea behind this special section originated during a series of oral history seminars and workshops, which I co-organized on behalf of the Warwick Oral History Network, between 2011 and 2013. The network’s first conference (‘Gender, Subjectivity and Oral History’), in particular, evoked many questions about the kind of relationships that make interviews possible, and the interviewer’s ambiguous position within the interview process. Keynote speaker Penny Summerfield, as well as other speakers and attendees, discussed a whole range of variables, such as age, ethnicity, religion and gender, and the particular dynamics these can bring to the interview, both facilitating and impeding the quest to find out more about a person’s life.

In this same period, Stacey Zembrzycki and Anna Sheftel published the volume Oral History off the Record: Toward an Ethnography of Practice (2013). The essays gathered here all focus on those aspects of oral history research that tend to remain unexplored in oral history scholarship, such as the relationships that unfold between interviewer and interviewee. Zembrzycki and Sheftel thus explain that the aim of the volume was ‘to explore how a more holistic approach to the interview might help us better understand the work we do and the people with whom we engage’.

Scholars in the field of oral history have continued in this direction, engaging more and more in discussions about the practical challenges of oral history research, and addressing issues such as intersubjectivity and ethics. Edited together with a member of the Warwick Oral History Network, Sofia Serenelli, the special section ‘Inside the Interview. The Challenges of a Humanistic Oral History Approach in the Deep Exchange of Oral History’ aims to contribute to this development, by investigating the complexity of the relationship between individual and collective memory, and the ambiguity of the interviewer’s own position as either insider or outsider in terms of age, nationality, ethnicity, or gender. Most importantly, it seeks to redefine oral history as a humanistic and processual methodology: one centered on the humanity of two human beings with different cultural and social backgrounds, and which considers the interview as intrinsically affected by what happens before, during, and after the interview.

We seek to redefine oral history as a humanistic and processual methodology: one centered on the humanity of two human beings with different cultural and social backgrounds, and which considers the interview as intrinsically affected by what happens before, during, and after the interview.

In sum, this special section analyzes the impact of self-reflexivity and personal identification on the interviewer-interviewee relationship within a variety of geographical environments and sociocultural contexts, focusing on memories of sensitive and traumatic events. Following Alessandro Portelli’s opening essay on the international development of oral history practice and the specific status of the interview, Angela Davis examines generational difference in the interview encounter, drawing on a wide body of oral history interviews that she conducted in Oxfordshire, and focused on the experience of sexuality and motherhood. Darshi Thoradeniya’s essay, which takes us to a totally different geographical context, focuses on her position as both insider and outsider in the interview process, which enabled her to both gain trust yet also posed important challenges. Anna Sheftel’s analysis of memories of atrocities among survivors of the Holocaust and the Bosnian war in Bosnia-Herzegovina raises ethical and methodological issues, in particular with regard to the limits of framing lives within the context of violence. Cahal McLaughlin, finally, analyzes the psychological and relational effects of video-recording, in his discussion of two documentary projects about the Troubles in Northern Ireland and apartheid in South Africa.

By disclosing interview experiences that reflect on the ways we listen to stories and shape them into narratives, we may come to a more profound understanding of oral history practice.

Andrea Hajek is a former British Academy postdoctoral fellow and a freelance academic editor. She is managing editor of the journal Memory Studies, and an associate editor of Modern Italy. She is also a founding member of the Oral History Network (University of Warwick), and an affiliate member of the Centre for Gender History (University of Glasgow). Her research interests include cultural and collective memory, gender and women’s history, Italian social movements, oral history, second-wave feminism, 1968 and the 1970s in Italy.

Featured image “Interview” is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-SA 2.0) by Flickr user Pierre Selim. We have cropped the image.