Author Interview: Eldad Ben Aharon on the Use of Oral History in the Study of International Relations

In his recent OHR article, “Doing Oral History with the Israeli Elite and the Question of Methodology in International Relations Research,” available in issue 47.1, Eldad Ben Aharon discusses the challenges and benefits of using oral history when researching the history of International Relations and diplomacy.

Why is oral history helpful for studying International Relations, especially when studying Israel?

Security agencies often conduct their operations in the shadows with the state’s sanction, being granted relatively unquestioned freedom to conduct their covert actions to protect a country’s security. This also directly limits the research options for International Relations (IR) historians because there is no access to those security agencies’ archival records, thus making oral history extremely valuable for scholars in the field.

The 12th director of the Mossad, Yossi Cohen and Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu. (Photo Credit: Miriam Alster/Flash90).

Regarding Israel, the country has been in a semi-permanent militaristic position, and it has always relied heavily on its intelligence agencies. Therefore, the dominance of rhetoric and actions around security and sovereignty in Israeli society, culture, politics, and, hence, its restrictive foreign policy is not at all surprising. My fieldwork, parts of which can be read in my new article in the OHR, leads me to argue that there is definite value in accessing the memories of the Israeli diplomatic/intelligence elites, because they can shed new light on actors, events, themes, and processes that characterize Israel’s foreign policy since 1948.

Why have historians of IR not typically used oral history to fill in details when censoring prohibits access to information?

There are two constraints: one, there is a generational barrier. Many of the IR historians that worked in the 1980s and 1990s and had a dominant voice in the field, did not believe in the use of oral history, meaning they have rejected memory as a source of knowledge about the past because of the assumed unreliability of memory itself. Subsequently, these historians mentored their students, the next generation of historians, teaching them to avoid oral history methodology as a reliable source, and this cycle has gone on and on. Generally, the new generation of IR historians has been more receptive of oral history but, most historians in the field still choose to rely on archival research.

Secondly, traditional archival research has seemed more reliable among IR historians, although we already know that all historical sources should be studied very carefully. As former US secretary of state Henry A. Kissinger noted in his biography “What is written in diplomatic documents never bears much relation to reality.” Even if Kissinger was exaggerating about the reduced importance of official diplomatic records, he was still making an important point. IR historians need to be very critical when analyzing any primary sources, not just oral histories but also official diplomatic records.

The problem begins when archival research has been controlled by strong censorship regulations of intelligence agencies. As a result, some topics/histories remain understudied because there is no access to formal documentation in archival records.

What is ‘clandestine diplomacy’ and how does it relate to your research?

Israeli Defence Force Chief of Staff Benny Gantz (2015-2011) with US Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Martin Dempsey (2011-2015), at a military base in Tel Aviv January 20, 2012. (Photo credit: Gideon Markowicz/Flash90)

Traditional diplomacy is mostly transparent to the public and covered by media outlets daily. By contrast, ‘clandestine diplomacy’ is part of the role that intelligence officials and their agencies play in modern diplomatic settings. The power balance between these two types of diplomacy varies by country and changes based on a country’s institutional traditions, its geography, geopolitics, and its perception of the nature of threats to its national security.

With regards to my article, in the U.S. and Israel for example, we can notice covert competition for diplomatic influence between the Ministry of Foreign Affairs or Department of State and corresponding intelligence agencies. Another factor which drives this competition, is that much of the Israeli political leadership began their careers in the military before ascending the rungs of political and/or executive power. Therefore, it is essential to interview these elite, who were part of milestone decisions and shaped the country’s history.

What are the barriers one would encounter when conducting oral interviews in IR research? Why are these barriers present and how can they be overcome?

There are two main barriers. First, as with any oral history project, one needs to understand the culture of the society the narrator is coming from. Cultural awareness is a significant factor because it affects the whole process of the oral history project. For example, how do you interpret a narrator’s initial hesitation to be interviewed, especially if they are a high ranking official? If they don’t say “yes” immediately, does that mean they are not interested or just can’t commit to the interview in advance? Would it be appropriate to try again or is the first refusal final?

Based on my experience as an Israeli who interviewed mainly Israeli diplomats, their first hesitation usually means that you might need a bit more effort to make contact, such as a second email (even third). Sometimes, even a phone call can help make the meeting happen. Also, it’s embedded in Israeli culture not to make appointments in advance and to play it by ear. Therefore, saying “call me when you are here, and we’ll fix something” (when you are visiting from abroad for a research trip) doesn’t mean they are not interested.

Secondly, it’s better to manage expectations about everything that ranges from signing a consent form, recording them or how long you estimate the interview will take. Most importantly, let them know what you intend to do with the outputs of the interview and to ask for their consent in advance to use the transcript in your publications. My experience tells me that most of them understand that their voice is extremely important to the research process of a certain topic/period.

If an interviewee is overly cautious or takes steps to ensure self-censoring, how can an interviewer help them overcome this caution?

I will tell you something that happened to me during my field research. In 2016, I retrieved a file from the Israeli State Archive with unclassified documents which become available for researchers only a year earlier. The documents recorded a secret summit that took place in 1987 in Ankara among Israeli and Turkish diplomats, in which they exchanged intelligence about terrorist organizations operating in the Middle East.

Both countries wanted to build a mutual counter-terror network, but also had further mutual interests to cooperate. However, the minutes, although 8 pages long, were quite vague, written by one diplomat who was present in the summit. Some details were missing regarding an Armenian organization, which was the primary focus of the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the core chapter of my doctoral thesis. I thought interviewing the Israeli participants at the summit and asking them tailored questions could cast more light about the important details of the summit.

Two of the diplomats had retired, and the one who wrote the minutes is still in active service; all of them are now in their 60s and 70s. I approached each of them by email asking their consent for an interview about the 1987 summit in Ankara. Initially, I explained that I retrieved the summit minutes in the Israeli State Archive and that their names were mentioned several times in the documents. Two of the diplomats who had retired, were quite suspicious of my request. So, they did not say anything immediately, but asked if I could share some details from the minutes. Once I gave them other names of individuals who were present in the summit, dates, and other relevant details they said, “sure let’s meet.” Both of them ended up being very kind and informative in their interviews.

Not everything went smoothly, however. The diplomat who documented the proceeding, who was recommended to me by his retired co-workers as a fair and thoughtful interviewee, declined my invitation, noting that he is still in active service.

Have there been any attempts on a large scale to challenge Israel’s censorship of diplomatic occurrences and communications?

23 May 1994: Rwandan Patriotic Front rebels load ammunition onto a truck. (Photo credit: Corinne Dufka/Reuters)

Yes, in the last few years there were two notable examples. In July 2018, several Israeli human rights activists, attorney Eitay Mack and historian Yair Auron, submitted a petition to the Israeli Supreme Court requesting to disclose four highly classified documents. Based on the Freedom of Information Law, 5758-1998, these documents record the talks between Israel, Turkey, and Azerbaijan and their objection to recognizing the 1915 Armenian genocide. The Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs strongly objected to the request and submitted the documents to the court. The petition was rejected by the Supreme Court, based on article (9A1) of the Freedom of Information Law (1998), which argues that state sensitive information cannot be disclosed if there is more than a reasonable doubt that revealing the information to the public could severely damage Israeli foreign policy and its national security.

Previously, in November 2016, these groups of activists submitted another petition to the Israeli Supreme Court regarding Israel trading arms with two countries, which perpetrated the genocides in Rwanda (1994) and Srebrenica (1995). The activists suspected that the arms that Israel sold to the perpetrators’ regimes were used during the genocides. Not surprisingly, this petition was also denied by the Supreme Court, based on the same arguments.

In my article, Israel’s arms trade history is one of the three short case studies discussed with my narrators. It demonstrates the opportunities oral history methodology gives us to study this sensitive and topical theme, which was obviously extremely censored.

How does an interviewee’s position during the performed clandestine diplomatic mission affect their recollection of the event in an interview?

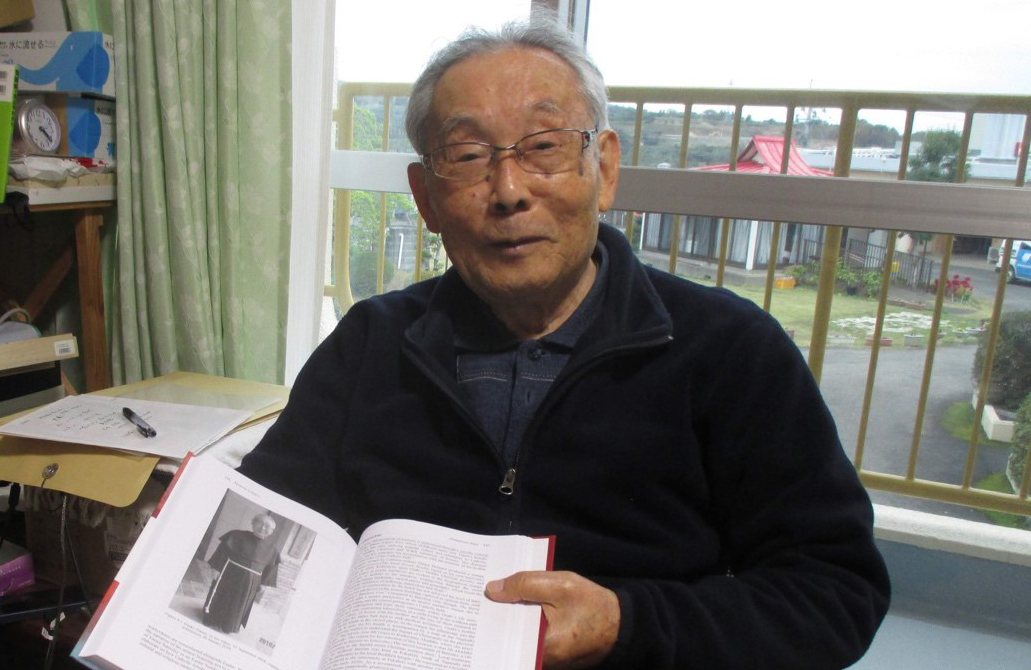

Well, that is a great question. Most of the Israeli elite I have interviewed—some of whom were very high-ranking officials, including the 9th director of the Mossad, Efraim Halevy—were proud to explain how close they were to the actual decision-making table. However, I also interviewed some lower-ranking officials and diplomats, who have overvalued their role in the process. That’s one of the dangers in oral history fieldwork which one needs to be totally aware of during the interview and was recently discussed in this journal. Actually, this might be a topic I will develop further for another research article.

The way to deal with this issue in my research project is to rely on the available documentation on specific decision making, which could cast initial light on who said what and who was really “in the room,” and by contrast, who was in the office behind a desk writing a telegram. When I came to analyze and interpret the transcripts of my interviews I had to be discerning when appraising what the narrators said. Thus, I always examined the interview transcript of one narrator vis-à-vis what other narrators said and carefully compared them with the available primary sources.

Are you planning to undertake further oral history projects in the future?

Yes, I’ll be starting a post-doctorate project later this year (2020) at the Peace Research Institute Frankfurt (PRIF) titled: “Nation Building and the Perpetrators of Genocide: Memory, State Security and the Cold War.” This project focuses on the early stages of the Cold War and the response of the three perpetrator states—Turkey, and the two Germanies (FRG and GDR)—to the UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (1948). By specifically examining how the memory of the Holocaust and the Armenian genocide was leveraged for state security, diplomacy, and governance, this project will contribute to understanding largely overlooked links between the memory of past crimes and perpetrator nation-building in the early stages of the Cold War. The project draws on two types of primary source: archival records and ‘elite oral interviews’. In this project, I will interview German and Turkish state officials and veteran diplomats about the ways in which the Holocaust and the Armenian genocide were used for nation-building. Although this is a well-researched field, I hope these interviews will cast new light about the competition between the two Germanies and their influence on the Cold War arms race and how the crimes of genocide were leveraged for nation-building and diplomacy. Furthermore, in the next few years, I hope to complete another series of interviews with Israeli elite and then publish a book about Israeli public and clandestine diplomacy.

Dr. Eldad Ben Aharon is a lecturer at LIAS Institute for Area Studies at Leiden University, the Netherlands. He obtained his PhD from Royal Holloway University of London in 2019. His doctoral thesis investigates why and how Israeli diplomats leveraged the contested memories of the Armenian genocide in key moments of the last decade of the Cold War. Dr. Ben Aharon specializes in the field of modern Middle East studies and the region’s diplomatic history during the Cold War. His research focuses on Israel’s foreign policy from 1948 to the present. His other main areas of interest are memory studies, Turkey’s foreign policy, the Middle East responses to Nazism and the Holocaust, comparative genocide studies, Arab Jews, and the theory and practice of oral history. He has published his research in Israel Journal of Foreign Affairs, Cold War History, Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies, and the British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies.

Featured image by Flickr user Tyler Hewitt, used with permission of a Creative Commons C.C. BY-NC 2.0 license.

Other photos courtesy of Eldad Ben Aharon.