How do the worlds of fishing and oral history overlap with each other? What are the similarities in story-telling? (oralhistoryreview)

Image: Second Annual Spring Fishing, by Project Healing Waters. CC-BY-ND-2.0 via Flickr.

Building community and ecoliteracy through oral history

By Andrew Shaffer

For our second blog post of 2015, we’re looking back at a great article from Katie Kuszmar in The Oral History Review (OHR), “From Boat to Throat: How Oral Histories Immerse Students in Ecoliteracy and Community Building” (OHR, 41.2.) In the article, Katie discussed a research trip she and her students used to record the oral histories of local fishing practices and to learn about sustainable fishing and consumption. We followed up with her over email to see what we could learn from high school oral historians, and what she has been up to since the article came out. Enjoy the article, and check out her current work at Narrability.com.

In the article, you mentioned that your students’ youthful curiosity, or lack of inhibition, helped them get answers to tough questions. Can you think of particular moments where this made a difference? Were there any difficulties you didn’t expect, working with high school oral historians?

One particular moment was at the end of the trip. Our final interview was with the Monterey Bay Aquarium’s (MBA) Seafood Watch public relations coordinator, who was kind enough to arrange the fisheries historian interviews and offered to be one of the interviewees as well. When we finally interviewed the coordinator, the most burning question the students had was whether or not Seafood Watch worked directly with fishermen. The students didn’t like her answer. She let us know that fishermen are welcome to approach Seafood Watch and that Seafood Watch is interested in fishermen, but they didn’t work directly with fishermen in setting the standards for their sustainable seafood guidelines. The students seemed to think that taking sides with fishermen was the way to react. When we left the interview they were conflicted. The Monterey Bay Aquarium is a well-respected organization for young people in the area. The aquarium itself is full of nostalgic memories for most students in the region who visit the aquarium frequently on field trips or on vacation. How could such a beloved establishment not consider fishermen voices, for whom the students had just built a newfound respect? It was a big learning moment about bureaucracy, research, empathetic listening, and the usefulness of oral history.

After the interview, when the students cooled off, we discussed how the dynamics in an interview can change when personal conflicts arise. The narrator may even change her story and tone because of the interviewer’s biases. We explored several essential questions that I would now use for discussion before interviews were to occur, for I was learning too. Some questions that we considered were: When you don’t agree with your narrator, how do you ask questions that will keep the communication safe and open? How do you set aside your own beliefs from the narrator, and why is this important when collecting oral history? In other words, how do you take the ego out of it?

Oral history has power in this way: voices can illuminate the issues without the need for strong editorializing.

The students were given a learning opportunity from which I hoped we all could gain insight. We discussed how if you can capture in your interview the narrator’s perspective (even if different than your own or other narrators for that matter), then the audience will be able to see discrepancies in the narratives and gather the evidence they need to engage with the issues. Hearing that Seafood Watch doesn’t work with fishermen might potentially help an audience to ask questions on a larger public scale. Considering oral history’s usefulness in engaging the public, inspiring advocacy, and questioning bureaucracy might be a powerful way for students to engage in the process without worrying about trying to prove their narrators wrong or telling the audience what to think. Oral history has power in this way: voices can illuminate the issues without the need for strong editorializing. This narrative power can be studied beforehand with samples of oral history, as it can also be a great way for students to reflect metacognitively on what they have participated in and how they might want to extend their learning experiences into the real world. Voice of Witness (VOW) contends that students who engage in oral history are “history makers.” What a powerful way to learn!

How did this project start? Did you start with wanting to do oral history with your students, or were you more interested in exploring sustainability and fall into oral history as a method?

Being a fisherwoman myself and just having started commercial fishing with my husband who is a fishmonger, I found my two worlds of fishing and teaching oral history colliding. Even after teaching English for ten years because of my love of storytelling, I have long been interested in creating experiential learning opportunities for students concerning where food comes from and sustainable food hubs.

Through a series of uncanny events connecting fishing and oral history, the project seemed to fall into place. I first attended an oral history for educators training through a collaborative pilot program created by VOW and Facing History and Ourselves (FHAO). After the training, I mentored ten seniors at my school to produce oral history Senior Service Learning Projects that ended in a public performance at a local art museum’s performance space. VOW was integral in my first year’s experience with oral history education. I still work with VOW and sit on their Education Advisory Board, which helps me to continue my engagement in oral history education.

In the same year as the pilot program with VOW, I attended the annual California Association of Teachers of English conference in which the National Oceanic Atmospheric Association’s (NOAA) Voices of the Bay (VOB) program coordinator offered a training. The training offered curriculum strategies in marine ecology, fishing, economics, and basic oral history skill-building. To record interviews, NOAA would help arrange interviews with local fishermen in classrooms or at nearby harbors. The interviews would eventually go into a national archive called Voices from the Fisheries.

The trainer for VOB and I knew many of the same fishermen and mongers up and down the central and north (Pacific) coast. I arranged a meeting between the two educational directors of VOW and VOB, who were both eager to meet each other, as they both were just firing up their educational programs in oral history education. The meeting was very fruitful for all of us, as we brainstormed new ways to approach interdisciplinary oral history opportunities. As such, I was able to synthesize curriculum from both programs in preparing my students for the immersion trip, considering sustainability as an interdependent learning opportunity in environmental, social, and economic content. When I created the trip I didn’t have a term for what the outcome would be, except that I had hoped they would become aware more aware of sustainable seafood and how to promote its values. Ecoliteracy was a term that came to fruition after the projects were completed, but I think it can be extremely valuable as a goal in interdisciplinary oral history education.

I believe oral history education can help to shape our students into compassionate critical thinkers, and may even inspire them to continue to interview and listen empathetically to solve problems in their personal, educational, and professional futures.

What pointers can you give to other educators interested in using oral history to engage their students?

With all the material out there, I feel that educators have ample access to help prepare for projects. In the scheme of these projects, I would advise scheduling time for thoughtful processing or metacognitive reflection. All too often, it is easy to focus on the preparation, conducting and capturing the interviews, and then getting something tangible done with it. Perhaps, it is embedded in the education world of outcome-based assessment: getting results and evidence that learning is happening. With high school students, the experience of interviewing is an extremely valuable learning tool that could easily get overlooked when we are focusing on a project

For example, on an immersion trip to El Salvador with my high school students, we were given an opportunity to interview the daughter of the sole survivor of El Mozote, an infamous massacre that happened at the climax of the civil war. The narrator insisted on telling us her and her mother’s story, despite the fact that she had just gotten chemotherapy the day prior. She said that her storytelling was therapeutic for her and helped her feel that her mother, who had passed away, and all those victims of the massacre would not die in vain. This was such heavy content for her and for us as her audience. We all needed to talk, be quiet about it, cry about it, and reflect on the value of the witnessing. In the end, it wasn’t the deliverable that would be the focus of the learning, it was the actual experience. From it, compassion was built in the students, not just for El Salvadorian victims and survivors, but on a broader scale for all people who face civil strife and persecution. After such an experience, statistics were not just numbers anymore, they had a human face. This, to date, for me has been the most valuable part of oral history education: the transformation that can occur during the experience of an interview, as opposed to the product produced from it. For educators, it is vital to facilitate a pointed and thoughtful discussion with the interviewer to hone in on the learning and realize the transformation, if there is one. The discussion about the experience is essential in understanding the value of the oral history interviewing.

Do you have plans to do similar projects in the future?

After such positive experiences with oral history education, I wanted a chance to actively be an oral historian who captures narratives in issues of sustainable food sources. I have transitioned from teaching to running my own business called Narrability with the mission to build sustainability through community narratives. I just completed a small project, in which I collected oral histories of local fishermen called: “Long Live the King: Storytelling the Value of Salmon Fishing in the Monterey Bay.” Housed on the Monterey Bay Salmon and Trout Project (MBSTP) website, the project highlights some of the realities connected to the MBSTP local hatchery net pen program that augments the natural Chinook salmon runs from rivers in the Sacramento area to be released into the Monterey Bay. Because of drought, dams, overfishing, and urbanization, the Chinook fishery in the central coast area has been deeply affected, and the need for a net pen program seems strong. In the Monterey Bay, there have been many challenges in implementing the Chinook net pen program due to the unfortunate bureaucracy of a discouraging port commission out of the Santa Cruz harbor. Because of the challenges, the oral histories that I collected help to illustrate that regional Chinook salmon fishing builds environmental stewardship, family bonding, community building, and provides a healthy protein source.

Through Narrability, I have also been working on developing a large oral history program with a group of organic farming, wholesale, and certification pioneers. As many organic pioneers face retirement, the need for their history to be recorded is growing. Irene Reti sparked this realization in her project through University of California, Santa Cruz: Cultivating a Movement: An Oral History Series on Organic Farming & Sustainable Agriculture on California’s Central Coast. Through collaboration with some of the major players in organics, we aim to build a comprehensive national collection of the history of organics for the public domain.

Is there anything you couldn’t address in the article that you’d like to share here?

I know being a teacher can be time crunched, and once interviews are recorded, students and teachers want to do something tactile with the interviews (podcasts/narratives/documentaries). I encourage educators to implement time to reflect on the process. I wished I would have done more reflective processing in this manner: to interview as a class; to discuss the experience of interviewing and the feelings elicited before, during and after an interview; to authentically analyze how the interviews went, including considering narrator dynamics. In many cases, the skills learned and personal growth is not the most tangible outcome. Despite this, I believe oral history education can help to shape our students into compassionate critical thinkers, and may even inspire them to continue to interview and listen empathetically to solve problems in their personal, educational, and professional futures. This might not be something we can grade or present as a deliverable, it might be a long-term effect that grows with a students’ life long learning.

Image Credit: Front entrance of the Aquarium. Photo by Amadscientist. CC by SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Using voice recognition software in oral history transcription

By Andrew Shaffer and Samantha Snyder

sat down with Samantha Snyder, a Student Assistant at the University of Wisconsin-Madison Archives, to talk about her work. From time to time, the UW Archives has students test various voice recognition programs, and for the last few months Samantha has been testing the software program Dragon NaturallySpeaking. This is an innovative way of processing oral histories, so we were excited to hear how it was going.

To start off, can you tell me a bit about the project you’re working on?

I started this project in June of 2014, and worked on it most of the summer. The interviews I transcribed included three sessions with a UW-Madison Teaching Assistant who participated in the 2011 Capitol Protests. There was some great content that was waiting to be transcribed, and I decided to dive right in. Each interview session was about fifty minutes.

I was asked to try out Dragon NaturallySpeaking. I had never heard of the software before, and was excited to be the one to test it out. What I didn’t realize is that there is quite the steep learning curve.

Sounds like it started off slow. What did it take to get the program working?

I spent quite a bit of time reading through practice exercises, which are meant to get the program to the point where it will recognize your voice. The exercises include things like Kennedy’s inaugural speech, children’s books, and cover letters. They were actually fun to read, but I knew I had to get down to business.

I loaded up the first interview into Express Scribe —

That’s a different program, right?

Yep, it allows you to slow down and speed up the interview, which I learned was absolutely necessary. With the programs finally up and running, I plugged in the start/stop pedal, opened a Word document and began. I immediately realized I had to slow the interview down to about 60% of its regular speed, because I was having a tough time keeping up.

Unfortunately, I think most oral historians are familiar with the drudgery of transcription. Do you think the program helped to make the process any easier?

The first interview session took me around five hours total to complete. This included editing the words and sentences that came out completely different than what I thought I had said clearly, and formatting the interview into its proper transcript form. During the first interview I tried using commands to delete and fix phrases, but I found it was easier to just going back through and edit after finishing the dictation. I was surprised at how long it took me to complete the first interview, and I was stressed that maybe this wasn’t worth it, and I should just listen and type without dictating.

For the second and third interview sessions, it became much easier, and Dragon began to recognize my voice, for the most part. It only took me around two hours to dictate and edit subsequent interviews, a much more manageable timeframe than five hours. I think using the pedal and Express Scribe made the process much easier, because I was able to slow down the interview as well as stop and start when needed. I definitely would recommend using similar products along with Dragon, because it does play audio but does not have the option to slow down or speed up the interview. Without the pedal and Express Scribe I think it would have taken me much longer! My pedal stopped working during one of my days working on transcribing, and it turned into a much more stressful process.

It sounds like the experiment was fairly success. Two hours to transcribe and edit a 50-minute interview doesn’t seem bad at all!

Overall I would say Dragon NaturallySpeaking is an innovative way to transcribe oral history interviews, but I wouldn’t say it is necessarily the most efficient. I would like to transcribe an interview of similar length by simply listening and typing to compare the amount of time taken, but I haven’t had a chance to do so yet.

Maybe we can get another review when you’ve had the chance to compare the methods. Any final thoughts?

I think I will still be transcribing by doing my old standard, listening and typing along with the recording. Speech recognition software is an innovative tool, but in the end there is still a long way to go before it replaces the traditional transcription process.

I’m sure we all look forward to the days when software can fully take over transcription. Thanks for your help, and for the excellent review!

If you’ve tried voice recognition software, or other creative oral history methods, share your results with us on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, even Google+.

Headline image credit: Listen. Image by Fe Ilya. CC BY-SA 2.0 via renneville Flickr.

Calling oral history bloggers – again!

By Andrew Shaffer

Last April, we asked you to help us out with ideas for the Oral History Review’s blog. We got some great responses, and now we’re back to beg for more! We want to use our social media platforms to encourage discussion within the broad community oral historians, from professional historians to hobbyists. Part of encouraging that discussion is asking you all to contribute your thoughts and experiences.

Whether you have a follow up to your presentation at the Oral History Association Annual Meeting, a new project you want to share, an essay on your experiences doing oral history, or something completely different, we’d love to hear from you.

Whether you have a follow up to your presentation at the Oral History Association Annual Meeting, a new project you want to share, an essay on your experiences doing oral history, or something completely different, we’d love to hear from you.

We are currently looking for posts between 500-800 words or 15-20 minutes of audio or video. These are rough guidelines, however, so we are open to negotiation in terms of media and format. We should also stress that while we welcome posts that showcase a particular project, we can’t serve as landing page for anyone’s kickstarter.

Please direct any questions, pitches or submissions to the social media coordinator, Andrew Shaffer, at ohreview[at]gmail[dot]com. You can also message us on Twitter (@oralhistreview) or Facebook.

We look forward to hearing from you!

Image credits: (1) A row of colorful telephones stands in Bangkok’s Hua Lamphong train station. Photo by Mark Fischer. CC BY-SA 2.0 via fischerfotos Flickr. (2) Retro Microphone. © Kohlerphoto via iStockphoto.

What we’re thankful for

By Andrew Shaffer and Troy Reeves

Since we’re still recovering from eating way too much yesterday, Managing Editor Troy Reeves and I would like to sit back and just share a few of the things we’re thankful for.

Troy Reeves:

Wow! So many things I’m thankful for, such as family, friends, pie, turkey, cranberries (basically just about every food associated with Thanksgiving). Except the marshmallows on top the yams – don’t get it, don’t like it.

Oh, right, this post should focus on the oral history-related thankful things. Well, it still comes back to friendship. I have been blessed over my now 15 years in the Oral History Association in building a cadre (cabal?) of colleagues who double as friends. And I leaned on these people early on to help us build our presence on OUPblog.

From our first post (thanks Sarah) through our longest podcast (thanks Doug) and several in-between (looking at you Steinhauer – for both posts – Wettemann, Morse and Corrigan, and Cramer), I feel like Joe Cocker (or Ringo Starr): I “get by with a little help from my friends.” (And I did not mention the law firm of Larson, Moye, and Sloan who helped us tease the 2013 OHA Conference.)

Last but not least, I’m thankful and grateful for the social media work of Caitlin Tyler-Richards. Even though I have full faith in Andrew, your presence will be missed. But I can always return to your last post, when I need my Caitlin fix.

So, there you go. And in case you are wondering: Yes, I turned my part of this into a homage to the Simpson’s cheesy-clip show.

Andrew Shaffer:

As a recent addition to the Oral History Review team, and a recent transplant to Wisconsin, there are a tonof things I’m thankful for.

First, I have to echo Troy in being thankful for Caitlin. She’s been immensely helpful in teaching me the social media ropes. #StillNotSureHowToHashtagProperlyThough

I’d like to name my favorite OHR blog posts, but there are just too many to list. I’m especially thankful, though, for people who are finding innovative ways to fund, record, and think deeply about oral history. It’s a privilege to be part of such an exciting field.

I met some amazing oral historians at the recent Oral History Association Annual Meeting, and I’m very grateful to all the people who helped to put on such a great conference.

I’m thankful to Troy for giving me a second interview, even after I showed up two hours late to the first one. Protip: When moving from the West Coast to the Midwest, make sure you update your calendar to the correct time zone.

And lastly, I should mention that I’m very thankful for my friends and family, even though most haven’t heard from me in a while!

———————-

Finally, after the recent polar vortex hitting us in Wisconsin, Troy and I are both veryhappy that next year’s OHA Annual Meeting will be in sunny Florida. Check out the Call For Papers here – we look forward to seeing you there!

We’ll be back with another blog post soon, but in the mean time, visit us on Twitter, Facebook, or Google+to tell us what you’re thankful for.

Happy Thanksgiving everyone!

Academics as activists: an interview with Jeffrey W. Pickron

By Jeffrey W Pickron

This week, we bring you an interview with activist and historian Jeffrey W. Pickron. He and three other scholars spoke about their experiences as academics and activists on a riveting panel at the recent Oral History Association Annual Meeting. In this podcast, Pickron talks to managing editor Troy Reeves about his introduction to both oral history and activism, and the risks and rewards of speaking out.

Heading image: Boeing employees protest meeting in Seattles City Hall Park, 1943 by Seattle Municipal Archives. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Sharecropper’s Troubadour: songs and stories from the 2014 OHA Annual Meeting | OUPblog

Sharecropper’s Troubadour: songs and stories from the 2014 OHA Annual Meeting | OUPblog

The 2014 Oral History Association Annual Meeting featured an exciting musical plenary session led by Michael Honey and Pat Krueger. They presented the songs and stories of John Handcox, the “poet laureate” of the interracial Southern Tenant Farmers Union, linking generations of struggle in the South through African American song and oral poetry traditions.

Recap of the 2014 OHA Annual Meeting

By Andrew Shaffer

Last weekend we were thrilled to see so many of you at the 2014 Oral History Association (OHA) Annual Meeting, “Oral History in Motion: Movements, Transformations, and the Power of Story.” The panels and roundtables were full of lively discussions, and the social gatherings provided a great chance to meet fellow oral historians. You can read a recap from Margo Shea, or browse through the Storify below, prepared by Jaycie Vos, to get a sense of the excitement at the meeting. Over the next few weeks, we’ll be sharing some more in depth blog posts from the meeting, so make sure to check back often.

We look forward to seeing you all next year at the Annual Meeting in Florida. And special thanks to Margo Shea for sending in her reflections on the meeting and to Jaycie Vos (@jaycie_v) for putting together the Storify.

Headline image credit: Madison, Wisconsin cityscape at night, looking across Lake Monona from Olin Park. Photo by Richard Hurd. CC BY 2.0 via rahimageworks Flickr.

The power of oral history as a history-making practice

By Andrew Shaffer

This week, we have a special podcast with managing editor Troy Reeves and Oral History Review 41.2 contributor Amy Starecheski. Her article, “Squatting History: The Power of Oral History as a History-Making Practice,” explores the ways in which an intergenerational group of activists have used oral history to pass on knowledge through public discussions about the past. In the podcast, Starecheski discusses her motivation for the project and her involvement in the upcoming Annual Meeting of the Oral History Association. Check out the podcast below.

You can learn more about the Annual Meeting of the Oral History Association in the Meeting Program. If you have any trouble playing the podcast, you can download the mp3.

Headline image credit: Courtesy of Amy Starecheski.

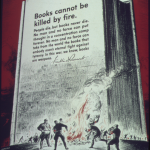

“Books cannot be killed by fire. People die, but books never die. No man and no force can put thought in a concentration camp forever. No man and no force can take from the world the books that embody man’s eternal fight against tyranny. In this war, we know, books are weapons.”

-Franklin D. Roosevelt

“Books are weapons in the war of ideas”, 1941 – 1945

From the series: World War II Posters, 1942 – 1945

Banned Books Week is September 21 – 27, 2014